One would imagine that François Guizot had known England well from an early age, as it was customary during the Restoration for distinguished young people to spend a period of time there. In fact, he knew England without ever having seen it, publishing in 1826-1827 the first two volumes of his History of the English Revolution without ever having set foot in the country. It was only at the end of February 1840, at the age of 52, that Guizot finally crossed the Channel when he was appointed French Ambassador in London by the Soult cabinet. The new Ambassador, arriving without his family, was already well-known and highly esteemed for his literary works on England. His personality was also much appreciated, “he has such a distinguished and pleasant manner”, wrote Lady Palmerston, the wife of the Foreign Secretary. In the French Embassy at Hertford House, he organised a suitable number of diplomatic dinners and receptions. The young Queen Victoria and the mature Guizot were very gracious to one another.

One would imagine that François Guizot had known England well from an early age, as it was customary during the Restoration for distinguished young people to spend a period of time there. In fact, he knew England without ever having seen it, publishing in 1826-1827 the first two volumes of his History of the English Revolution without ever having set foot in the country. It was only at the end of February 1840, at the age of 52, that Guizot finally crossed the Channel when he was appointed French Ambassador in London by the Soult cabinet. The new Ambassador, arriving without his family, was already well-known and highly esteemed for his literary works on England. His personality was also much appreciated, “he has such a distinguished and pleasant manner”, wrote Lady Palmerston, the wife of the Foreign Secretary. In the French Embassy at Hertford House, he organised a suitable number of diplomatic dinners and receptions. The young Queen Victoria and the mature Guizot were very gracious to one another.  One night in June, he came across her in her nightgown in one of the bedrooms of Windsor Castle. He discovered Westminster with Macaulay, the brilliant historian, visited Eton College and its boat races on the Thames, went to services in Saint Paul’s cathedral with the Bishop of London, addressed the Royal Academy of Arts in French with “the resounding success that accompanies M. Guizot everywhere he goes in London” and at Mansion House with Prince Albert, spoke in English at a meeting against the slave trade, where “my name and my person were much applauded”. He even risked placing bets on races at Epsom. He made strong links with the British aristocracy to which he was very attracted. When he left at the end of October, Lady Palmerston wrote: “We are extremely sorry to lose him. Everything about him denotes a gentleman, in the profoundest sense of the term.” These eight months as Ambassador will provide the material for one of the most touching chapters of his Memoirs.

One night in June, he came across her in her nightgown in one of the bedrooms of Windsor Castle. He discovered Westminster with Macaulay, the brilliant historian, visited Eton College and its boat races on the Thames, went to services in Saint Paul’s cathedral with the Bishop of London, addressed the Royal Academy of Arts in French with “the resounding success that accompanies M. Guizot everywhere he goes in London” and at Mansion House with Prince Albert, spoke in English at a meeting against the slave trade, where “my name and my person were much applauded”. He even risked placing bets on races at Epsom. He made strong links with the British aristocracy to which he was very attracted. When he left at the end of October, Lady Palmerston wrote: “We are extremely sorry to lose him. Everything about him denotes a gentleman, in the profoundest sense of the term.” These eight months as Ambassador will provide the material for one of the most touching chapters of his Memoirs.

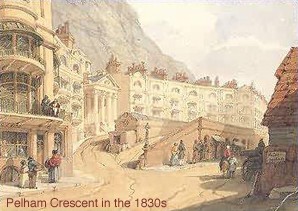

It was in quite different circumstances that Guizot returned to London at the beginning of March, 1848. He was now an exile. Taken in on his arrival by his close friend Mrs Sarah Austin, he first lived in Bryanston Square, where he was reunited with his children, then moved to 21 Pelham Crescent, Brompton, which was then in the suburbs of London. His mother joined him there but died on March 31. She was buried at the Kensal Green cemetery, where her grave can still be found.

It was in quite different circumstances that Guizot returned to London at the beginning of March, 1848. He was now an exile. Taken in on his arrival by his close friend Mrs Sarah Austin, he first lived in Bryanston Square, where he was reunited with his children, then moved to 21 Pelham Crescent, Brompton, which was then in the suburbs of London. His mother joined him there but died on March 31. She was buried at the Kensal Green cemetery, where her grave can still be found. Guizot quickly remade contact with the society he had left in 1840: Macaulay, Henry Hallam, Henry Reeve, Lord Holland and particularly his dear friend Lord Aberdeen. Charles Greville, Clerk of the Queen’s Privy Council, describes him as follows: “He goes everywhere, is in good form and is putting on a brave face. Everyone is very polite to him and he appreciates the kindness of this welcome.” It is in Brompton that he writes two important books, On Democracy in France, a vigorous political essay, and Why did the English Revolution succeed? a historical study that was not unrelated to the current situation. Oxford University received him triumphantly and offered, unsuccessfully, to elect him as professor.

Guizot quickly remade contact with the society he had left in 1840: Macaulay, Henry Hallam, Henry Reeve, Lord Holland and particularly his dear friend Lord Aberdeen. Charles Greville, Clerk of the Queen’s Privy Council, describes him as follows: “He goes everywhere, is in good form and is putting on a brave face. Everyone is very polite to him and he appreciates the kindness of this welcome.” It is in Brompton that he writes two important books, On Democracy in France, a vigorous political essay, and Why did the English Revolution succeed? a historical study that was not unrelated to the current situation. Oxford University received him triumphantly and offered, unsuccessfully, to elect him as professor.

After returning to France in July 1849, Guizot returned several times to England, notably visiting the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in 1851. Each visit enabled him to confirm his attachment to British society, which earned him the nickname “Lord Guizot” during the period of the first entente cordiale. A few months before his death, he wrote: “I also live in England. It is a lot to have two lives and almost two homelands.” A commemorative plate has recently been put on the house in which he lived during his exile.

After returning to France in July 1849, Guizot returned several times to England, notably visiting the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in 1851. Each visit enabled him to confirm his attachment to British society, which earned him the nickname “Lord Guizot” during the period of the first entente cordiale. A few months before his death, he wrote: “I also live in England. It is a lot to have two lives and almost two homelands.” A commemorative plate has recently been put on the house in which he lived during his exile.