“I will not finish these pages without naming my friends that still remain. I wish them to know how much their friendship has meant to me and ask them not to forget me when I am no longer here. I therefore pray that this message be passed on to M. le duc de Broglie and M. Guizot.” On Prosper de Barante’s death in 1866, Guizot inserted this passage from his friend’s will into the frame of his photo that was always in a prominent position in his study at Val-Richer, close to the photo of Victor de Broglie. This friendship went back some fifty years or more and although never totally intimate, remained steady and untroubled. Guizot once wrote in 1865 that there was “a little jealousy” involved. He is indulging himself, as the esteem and admiration that Barante had for him was simply recognition of his intellectual and political superiority. He himself had no desire to exercise power, even though he was in a position to do so – a choice that Guizot found hard to conceive.

“I will not finish these pages without naming my friends that still remain. I wish them to know how much their friendship has meant to me and ask them not to forget me when I am no longer here. I therefore pray that this message be passed on to M. le duc de Broglie and M. Guizot.” On Prosper de Barante’s death in 1866, Guizot inserted this passage from his friend’s will into the frame of his photo that was always in a prominent position in his study at Val-Richer, close to the photo of Victor de Broglie. This friendship went back some fifty years or more and although never totally intimate, remained steady and untroubled. Guizot once wrote in 1865 that there was “a little jealousy” involved. He is indulging himself, as the esteem and admiration that Barante had for him was simply recognition of his intellectual and political superiority. He himself had no desire to exercise power, even though he was in a position to do so – a choice that Guizot found hard to conceive.

Prosper Brugière, made Baron de Barante by Imperial decree renewed under the Restoration, born in 1782 and descending from a family belonging to the old Auvergne bourgeoisie – the Barante estate is not far from Thiers – had begun a promising career at a very early age. His father Claude-Ignace, imprisoned during the Reign of Terror and saved in extremis by the Thermidor conspiracy, had been appointed a Prefect at the beginning of the Consulate, opening up the way for his son. An auditor in the Council of State in 1806, Prosper became sub-Prefect of Bressuire the following year, then Prefect of the Lower Loire in 1809 at the age of 26. In March 1815, during the Hundred Days, he resigned and adopted a position that had in fact always been his – a constitutional monarchist. A few months later he was appointed Secretary General in the Ministry of the Interior, a position occupied by Guizot under the First Restoration, who then became his counterpart in the Ministry of Justice. This was when they really made one another’s acquaintance.

They had perhaps already seen one another from a distance. In 1811, Barante had married the beautiful and pious Césarine d’Houdetot, the granddaughter of Rousseau’s lady friend, whose salon Guizot often visited, thus officially putting an end to a somewhat tumultuous youth. In 1804, when his father was Prefect of Geneva, he had met Germaine de Staël and fallen in love with her to the point of wanting to marry her, much to his father’s anger: “everything is believable, everything is possible in the horrible folly this woman has led you into” he wrote to him in 1806. Failing this, he transferred his affections to Juliette Récamier. Remusat related: “He was in love with Mme Récamier to the point of asking her to divorce. He wanted to marry her.

They had perhaps already seen one another from a distance. In 1811, Barante had married the beautiful and pious Césarine d’Houdetot, the granddaughter of Rousseau’s lady friend, whose salon Guizot often visited, thus officially putting an end to a somewhat tumultuous youth. In 1804, when his father was Prefect of Geneva, he had met Germaine de Staël and fallen in love with her to the point of wanting to marry her, much to his father’s anger: “everything is believable, everything is possible in the horrible folly this woman has led you into” he wrote to him in 1806. Failing this, he transferred his affections to Juliette Récamier. Remusat related: “He was in love with Mme Récamier to the point of asking her to divorce. He wanted to marry her.  He was very unhappy. One evening, Mme de Staël, feeling sorry for him and after having tried to console him, thought that the best thing to do would be to immediately make him sleep with her. He told me this himself.” The two women remained his friends, as did later the Duchesse de Broglie and especially the Duchesse de Dino, no one knowing exactly the extent of his relationship with her. This he had in common with Guizot: they were both very attractive to great ladies, sometimes the same ones, principally through the charm of their conversation. It would appear that Barante was incomparable in this domain and for a long time, he was also a very good-looking man.

He was very unhappy. One evening, Mme de Staël, feeling sorry for him and after having tried to console him, thought that the best thing to do would be to immediately make him sleep with her. He told me this himself.” The two women remained his friends, as did later the Duchesse de Broglie and especially the Duchesse de Dino, no one knowing exactly the extent of his relationship with her. This he had in common with Guizot: they were both very attractive to great ladies, sometimes the same ones, principally through the charm of their conversation. It would appear that Barante was incomparable in this domain and for a long time, he was also a very good-looking man.

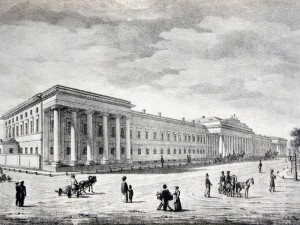

Under the Restoration, Barante and Guizot led parallel careers, except that the former was a Deputy from 1815 -1816, then sat in the House of Peers from 1819 onwards. Councillors of State, high ranking civil servants, they supported the liberal policy of the first ministries forming in 1817 the nucleus of the “Doctrinaires” group under the leadership of Royer-Collard, about whom Barante later wrote a two-volume book. In 1820, they were both dismissed from the Council of State and then dedicated themselves to writing and history, Barante publishing a translation of the works of Schiller, then a monumental Histoire des ducs de Bourgogne de la maison de Valois, earning him a seat in the Académie Française in 1828. Each wrote in the press very favourable reviews of the other’s books and when Guizot founded the Revue Française in 1828, Barante was one of his most active collaborators. They were both in perfect harmony in their thoughts and actions.  They remained so under the July Monarchy, when Barante was appointed Ambassador in Turin, then in St Petersburg in 1835. When, in October 1840, Guizot took over the Foreign Ministry, Barante wrote to him: “My dear friend, I am now under your orders and I will find myself writing official letters to you, having seen our more intimate correspondence sadly coming to an end”. This soon started up again, as in 1842 a diplomatic incident with Russia meant that Barante could not return to his post in St Petersburg, although he held the office until 1848. He was often resident in Barante, as President of the General Council of the Puy-de-Dôme, and Guizot wrote, “he was for me a distant spectator, clairvoyant, wise, cool-headed, and his letters conveyed both his judicious concerns and his affectionate encouragements”. He did not agree with his friend’s behaviour in the 1838-1839 coalition and in September 1847, expressed his worries about “this concern for private interests, these distributions of favours and positions, and particularly this weakness for the demands of deputies that have been more or less necessary to obtain a majority.” For Prosper de Barante had extremely high moral standards and was a true liberal. Guizot welcomed his advice but did not always follow it, and he looked after the careers of his sons, making the eldest, Prosper, a sub-Prefect in Boussac then a Prefect in the Ardèche. The younger son, Ernest, was made a Secretary in the Embassy in Dresden. The latter caused his parents a great deal of worry, as he was subject to fits of madness that necessitated his internment and brought on his death in 1859. Barante and Guizot shared a very strong sense of family.

They remained so under the July Monarchy, when Barante was appointed Ambassador in Turin, then in St Petersburg in 1835. When, in October 1840, Guizot took over the Foreign Ministry, Barante wrote to him: “My dear friend, I am now under your orders and I will find myself writing official letters to you, having seen our more intimate correspondence sadly coming to an end”. This soon started up again, as in 1842 a diplomatic incident with Russia meant that Barante could not return to his post in St Petersburg, although he held the office until 1848. He was often resident in Barante, as President of the General Council of the Puy-de-Dôme, and Guizot wrote, “he was for me a distant spectator, clairvoyant, wise, cool-headed, and his letters conveyed both his judicious concerns and his affectionate encouragements”. He did not agree with his friend’s behaviour in the 1838-1839 coalition and in September 1847, expressed his worries about “this concern for private interests, these distributions of favours and positions, and particularly this weakness for the demands of deputies that have been more or less necessary to obtain a majority.” For Prosper de Barante had extremely high moral standards and was a true liberal. Guizot welcomed his advice but did not always follow it, and he looked after the careers of his sons, making the eldest, Prosper, a sub-Prefect in Boussac then a Prefect in the Ardèche. The younger son, Ernest, was made a Secretary in the Embassy in Dresden. The latter caused his parents a great deal of worry, as he was subject to fits of madness that necessitated his internment and brought on his death in 1859. Barante and Guizot shared a very strong sense of family.

The Revolution of 1848 lead to his immediate and definitive departure from public affairs. Neither the Republic nor the Second Empire had any attraction for him. He settled down with the admirable Césarine in a studious, sociable and charitable retirement, residing often in Barante, doing many good works and occasionally visiting the Académie Française and the Société de l’Histoire de France, of which he had been President since its creation in 1833, on the instigation of Guizot. They dined together frequently at one another’s residences or elsewhere when they were in Paris and their friendship not only never faltered but became almost tender. On the death of the Princess von Lieven in 1857, Guizot wrote to Barante: “My dear friend, if you were here, you would perhaps be the person with whom I could talk most openly”… The two last letters published, written and received by Barante are to and from Guizot in June 1866. He died in November. The following year, Guizot published a very longobituary on his friend in the Revue des Deux Mondes, repeated in his Mélanges biographiques in 1868 and declared before the General Assembly of the Société de l’Histoire de France, where he succeeded him as President: “A strong and unmoving friendship is a rare happiness when everything around it is unsteady and changing. And the roots of the friendship that united M. de Barante and myself are those that one can find traces of at each step, throughout the years: there was a constant and profound similitude in our inclinations and our work, our ideas and our careers. We have, both of us, seriously loved and served letters and public life.”

The correspondence between Guizot and Barante has been published in part in the eight volumes of the Souvenirs du baron de Barante, edited between 1890 and 1901 by his grandson Claude. These 171 letters form a magnificent document.