The first “entente cordiale” between France and England was brought about by a very strong symbolic gesture – Queen Victoria’s visit to King Louis-Philippe at the Château d’Eu in Normandy from the 2nd to the 7th of September 1843. She was the first British monarch to go to France since Henry VIII. This demonstration of friendship was even more remarkable as three years earlier, the two countries had been on the brink of war over the Far East question, public opinion then displaying strong feelings of resentment on both sides of the Channel.

The first “entente cordiale” between France and England was brought about by a very strong symbolic gesture – Queen Victoria’s visit to King Louis-Philippe at the Château d’Eu in Normandy from the 2nd to the 7th of September 1843. She was the first British monarch to go to France since Henry VIII. This demonstration of friendship was even more remarkable as three years earlier, the two countries had been on the brink of war over the Far East question, public opinion then displaying strong feelings of resentment on both sides of the Channel.  The appointment of a new government on October 29, 1840 with François Guizot as Foreign Secretary was seen to be the first sign of reconciliation. In August 1841, George Hamilton Gordon, Earl of Aberdeen, replaced Henry Temple, Viscount Palmerston, as head of the Foreign Office in a conservative cabinet lead by Robert Peel. The quality of relations between London and Paris soon improved. The friendship between the two monarchs, demonstrated by the King of France’s visit to the Queen of England at Windsor in October 1844 and Queen Victoria’s lightning visit to Eu in September 1845, was enhanced by the strong ties that were being formed between the bourgeois French Minister and the Scottish Lord.

The appointment of a new government on October 29, 1840 with François Guizot as Foreign Secretary was seen to be the first sign of reconciliation. In August 1841, George Hamilton Gordon, Earl of Aberdeen, replaced Henry Temple, Viscount Palmerston, as head of the Foreign Office in a conservative cabinet lead by Robert Peel. The quality of relations between London and Paris soon improved. The friendship between the two monarchs, demonstrated by the King of France’s visit to the Queen of England at Windsor in October 1844 and Queen Victoria’s lightning visit to Eu in September 1845, was enhanced by the strong ties that were being formed between the bourgeois French Minister and the Scottish Lord. It was the latter who coined the phrase “a cordial good understanding” in October 1843 echoed by Louis-Philippe in his speech inspired by Guizot where he referred to “une sincère amitié” and a spirit of “cordiale entente”. Victoria used these same expressions before Parliament in February 1844. The Entente Cordiale was not an alliance confirmed by a treaty, but a state of mind defined as follows by the French minister on January 22, 1844: “On certain questions, the two countries have understood that they can agree and act together, without a formal undertaking and without renouncing any aspect of their freedom.” It was soon to be based on a very original approach: the two colleagues established a private correspondence, unknown to their other ministers, parliaments and diplomatic agents, the aim of which was described by Guizot in a letter to Aberdeen on March 9, 1844: “We basically both want the same things. So we can tell each other everything. We are honest men. Therefore we can always believe one another.” And this is indeed what they did, until the departure of Aberdeen in June 1846. This method enabled them to resolve difficulties and overcome crises that could easily have degenerated: Right of Search on their respective ships to prevent slave trading; the protectorate established by France in Tahiti, with what was known as the “Pritchard affair” unleashing passions on both sides; French intervention in Morocco; the rivalry between ambassadors in Athens and Madrid, etc. Each time, the personal contacts between the two ministers and sometimes very frank discussions always managed to douse the flames and preserve peace, which was the basis of their policy. To do so, they had to face attacks from their parliamentary oppositions and sometimes the incomprehension of their own political friends. Whilst Aberdeen was accused of “kissing the ground in front of the French ally”, his counterpart had to endure the nickname “Lord Guizot”. One particularly sensitive question, the marriages of the young Spanish Queen Isabella and her sister, for which affair France and England had long been rivals in Madrid, seemed to have been settled by a satisfactory compromise when Peel’s government was overthrown in June 1846. Palmerston, who had replaced Aberdeen, decided on a confrontation with Paris. Guizot, who had always had a bone of contention with him, took up the glove and in a somewhat brutal fashion concluded the marriages to the advantage of France. In October, the Entente Cordiale was over. However, France and England were never at war again.

It was the latter who coined the phrase “a cordial good understanding” in October 1843 echoed by Louis-Philippe in his speech inspired by Guizot where he referred to “une sincère amitié” and a spirit of “cordiale entente”. Victoria used these same expressions before Parliament in February 1844. The Entente Cordiale was not an alliance confirmed by a treaty, but a state of mind defined as follows by the French minister on January 22, 1844: “On certain questions, the two countries have understood that they can agree and act together, without a formal undertaking and without renouncing any aspect of their freedom.” It was soon to be based on a very original approach: the two colleagues established a private correspondence, unknown to their other ministers, parliaments and diplomatic agents, the aim of which was described by Guizot in a letter to Aberdeen on March 9, 1844: “We basically both want the same things. So we can tell each other everything. We are honest men. Therefore we can always believe one another.” And this is indeed what they did, until the departure of Aberdeen in June 1846. This method enabled them to resolve difficulties and overcome crises that could easily have degenerated: Right of Search on their respective ships to prevent slave trading; the protectorate established by France in Tahiti, with what was known as the “Pritchard affair” unleashing passions on both sides; French intervention in Morocco; the rivalry between ambassadors in Athens and Madrid, etc. Each time, the personal contacts between the two ministers and sometimes very frank discussions always managed to douse the flames and preserve peace, which was the basis of their policy. To do so, they had to face attacks from their parliamentary oppositions and sometimes the incomprehension of their own political friends. Whilst Aberdeen was accused of “kissing the ground in front of the French ally”, his counterpart had to endure the nickname “Lord Guizot”. One particularly sensitive question, the marriages of the young Spanish Queen Isabella and her sister, for which affair France and England had long been rivals in Madrid, seemed to have been settled by a satisfactory compromise when Peel’s government was overthrown in June 1846. Palmerston, who had replaced Aberdeen, decided on a confrontation with Paris. Guizot, who had always had a bone of contention with him, took up the glove and in a somewhat brutal fashion concluded the marriages to the advantage of France. In October, the Entente Cordiale was over. However, France and England were never at war again.

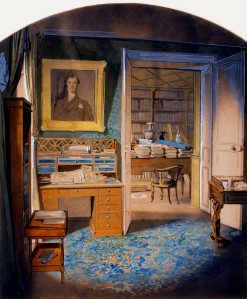

On top of Guizot’s desk, one can see the copy by Henry Landseer of a painting from Thomas Lawrence representing Lord Aberdeen.

The Entente Cordiale was the basis of a true and profound friendship between Guizot and Aberdeen, which on Guizot’s side, took on an affectionate, even passionate aspect: “All yours from the very depths of my soul”, he wrote at the end of a letter in July 1846. In 1847, they exchanged portraits, which they hung in their respective drawing rooms. This wonderful relationship never varied for one instant and lasted until the death of Aberdeen in 1860. “He loved me and I loved him”, Guizot wrote on this occasion. “A true, intimate, and I would even say tender friendship, if such could be said between men.”